Before the bone conduction implant, there was a rabbit, a titanium screw, and a visionary physician from Sweden, who dared to turn against the conventional medical wisdom of the 1950’s when he made an incredible discovery. Osseointegration was a serendipitous finding that started a healthcare revolution by creating life-changing industries that would benefit millions of people around the world.

In today’s medical technology and biomedical engineering, the applications of osseointegration spread across dental implants, bone conduction hearing, reconstructive surgery, and limb and craniofacial prosthetics.

Let’s take a trip back, before the age of the Internet, when technology was fascinating, scary, and easily misunderstood. We turn the clock some 50 years back, when Neil Armstrong was taking the first steps on the Moon, when the Beatles became a world sensation, when professor Brånemark was experimenting with rabbits, and when a mother from Gothenburg was hoping she’d one day be able to hear her daughter’s voice.

Against all odds: resisting resistance

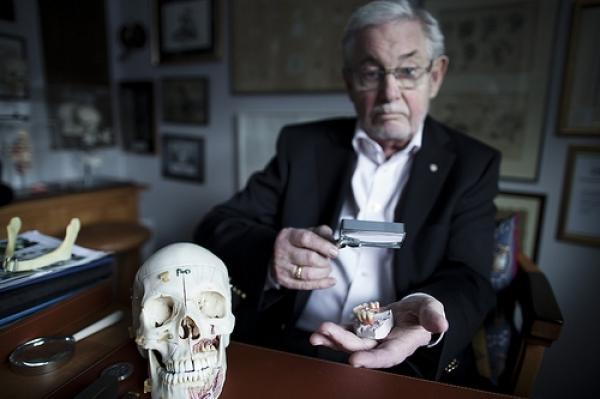

Per-Ingvar Brånemark is known today as the father of the modern dental implant. He was a physician and professor from Sweden, who studied rheology at the University of Lund, before he became a Professor of Anatomy at the University of Gothenburg.

Brånemark’s scientific interest was bone, or more specifically, how blood flow affects bone healing. In 1952, while conducting a study on the anatomy of blood flow, he placed a titanium optic chamber in a rabbit’s tibia and fibula. As he tried to remove the titanium device, he realised in awe that the bone tissue had fused with the metal, a process he termed “osseointegration”. He soon recognised the potential of the newly discovered process, and moved on to research its properties and stability.

At a time when the scientific consensus was that living tissue would reject foreign bodies, Brånemark’s discovery that bone fused with titanium caused a roar in the scientific society. Osseintegration was considered blasphemous, and as a consequence, Brånemark’s applications for research grants to study bone anchored implants were repeatedly declined in the 1960’s.

Despite the reluctance and rejection he’d received from his peers, Brånemark continued to study osseointegration. From rabbits, he moved on to dogs, before he started testing the process on humans. He wanted to see whether commercially pure titanium would cause any reactions, so he implanted titanium in volunteer students and observed them over several months. As osseointegration took place, Brånemark could not note any adverse reactions.

From dental implants to hearing systems

In 1966, osseointegration was first applied to oral implants using titanium fixtures which integrated with the jawbone. Once the implant was in place, Brånemark and his research team needed to know whether it had osseointegrated or only mechanically retained in the bone from the surgery. To check how well the implant had fused with the bone and how stable it was, the team attached a vibrating device to the implant – a standard bone conductor, and the feedback they received from the patient was astonishing.

The patient could hear high levels of sound, although he suffered from hearing loss. The sound was being transferred via the implant! Yet another breakthrough that was going to improve the lives of thousands of people who could not be treated with conventional hearing aids. The first step toward the bone conduction hearing implant had been taken. A young and eager PhD student named Anders Tjellström, known today as the pioneer of the bone conduction hearing implant, was one of Brånemark’s research team when this momentous discovery took place.

In 1977, after conducting multiple hearing tests based on Brånemark’s suggestion to place a titanium implant in the bone behind the ear, the first bone conduction implant was performed by then surgeon Anders Tjellström. Mona Andersson was the first patient in the world to regain access to sound via a bone conduction implant, after struggling with hearing loss for more than 30 years.

First scientific acknowledgement to come after more than 20 years

Brånemark was convinced that the titanium implants could be used for dental restoration, help people with hearing impairment who couldn’t benefit from conventional hearing aids, and also for other reconstructive surgeries such as limb and craniofacial prosthetics.

As his methods were systematically proven, he started receiving recognition in the scientific world. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare finally approved his method in the 1970’s. In 1982, Brånemark’s case for osseointegration, presented at a conference in Toronto, won worldwide recognition, marking a turning point in his career.

Professor Brånemark’s achievements have been honored with many distinctions, including the Swedish Engineering Academy’s medal for technical innovation, the Swedish Society of Medicine’s Söderberg Prize, and the European Inventor Award for Lifetime Achievement.